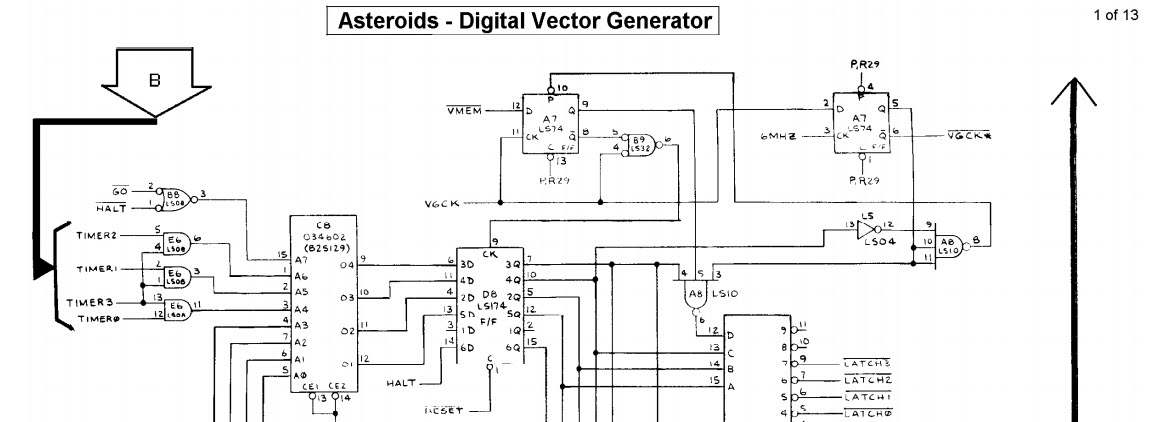

Digital Vector Generator (DVG)

There is a lot of info here:

http://www.philpem.me.uk/elec/vecgen.pdf

This info talks about the global scale factor allowing multiply and divide.

Follow the schematics here to figure it out:

http://www.jmargolin.com/vgens/aster.pdf

Vector Graphics

Modern computers use raster graphics. The monitor display is essentially a giant two dimensional matrix of dots (a dot matrix). The states of these dots must be configured a giant buffer in memory. The more dots you have on the screen and the more color values each dot can take the more memory you need.

Memory was expensive in the arcade era. Some games like Asteroids use a vector-display mechanism. The display hardware reads a list of lines from memory and actually steers the monitor's beam around to draw lines one after the other on the screen. These lines were super-crisp compared to the blocky lines drawn on low-resolution raster displays. The vector display doesn't need much memory -- just a list of lines.

But in the end all your program can draw is a bunch of lines.

Detailed information on the DVG from Asteroids: http://www.jmargolin.com/vgens/aster.pdf

Memory Layout

The DVG reads lines from an 8K bank of memory. The first 4K is RAM. The last 4K is ROM containing vector sequences for the game: asteroids, letters and numbers, ships, UFOs, etc. The "display list" is much more than a list of lines. It is actually an opcode language that includes the ability to jump to one of these ROM subroutines and then back to the next command.

The main program fills the display RAM with "Move to" commands and "subroutine" commands to draw all the game object lines on the screen. The last command in RAM is the "Halt" command that tells the display hardware it has reached the end of the list.

The DVG and main CPU share this 8K area of memory. The main CPU writes to it and the vector generator reads from it. The main CPU writes to this area as individual bytes. But the DVG itself reads the area as two-bytes words. The bytes are read little-endian -- least significant byte first.

For instance, the main CPU writes four bytes to the shared RAM as follows:

1000: BF 36 BF 06

The DVG would fetch these bytes as two words LSB first:

0800: 36BF 06BF

Screen Geometry

The DVG keeps up with a current (x,y) cursor coordinate. (0,0) is the lower left corner of the display. (1023,1023) is the upper right corner of the display.

Vectors are defined as a deltaX, deltaY, and intensity (0 through 15). The line intensity (brightness) increases with 0 being "off" and 15 being the brightest. Intensity 0 can be used to move the (x,y) cursor without drawing a line.

The deltas can be positive or negative to draw a line in any direction from the current cursor location.

In addition to the (x,y) cursor, the DVG keeps a scaling-factor that can be changed before calling a ROM routine. This allows the same asteroid image to be drawn in different sizes. The scaling-factor remains in effect until you change it.

The scaling-factor is a power-of-two divisor:

0 /512 1 /256 2 /128 3 /64 4 /32 5 /16 6 /8 7 /4 8 /2 9 /1

Imagine a sequence that draws a square like this:

MoveTo(0,0,9) ; Bottom left corner of screen, global-scale of 9 (divide-by-one) LineTo(1023,0) ; To the right 1023 LineTo(0,1023) ; Up 1023 LineTo(-1023,0) ; Left 1023 LineTo(0,-1023) ; Down 1023

If the scale was set to 9 then all the values get divided by 1 (unchanged). The square bounds the entire screen. But if the scale was set to 8 then the values get divided by 2 and the square wraps the lower left quadrant of the screen. A scale-factor of 0 divides everything by 512 -- turning those 1023's into 2's. That would draw a tiny box in the bottom left corner of the screen.

Vector Specification

A vector has a deltaX, deltaY, and an intensity. It also has its own "local" scale factor. This "local" scale-factor is added to the global scale-factor to make a "total" scale-factor used in rendering the vector.

Take these two lines for instance. Assume the global scale-factor is 0:

dx dy int scale LineTo (800, 0, 15, 5) LineTo (1600, 0, 15, 4)

The first line is drawn 50 units to the right since the total scale factor is 0+5 = 5 (divide-by-16). 800/16=50.

The second line has a total factor of 0+4 = 4 (divide by 32). It is also drawn 50 units to the right. 1600/32=50.

If the global scale-factor were set to 4 then the first line would be drawn with a factor of 5+4=9 (divide-by-one). The line would be 800 units long.

The second line would be drawn with a factor of 4+4=8 (divide-by-two). The line would be 800 units long.

Thus the added global scale-factor of 4 has made the sequence of lines 16 times larger.

DVG Opcodes

Most DVG commands are one word (two bytes) long. Some are two words (four bytes).

The upper nibble of the first word is the command.

0 - 9 : VEC -- a full vector command

A : LABS -- set the current (x,y) and global scale-factor

B : HALT -- end of commands

C : JSR -- jump to a vector program subroutine

D : RTS -- return from a vector program subroutine

E : JMP -- jump to a location in the vector program

F : SVEC -- a short vector command

VEC

Draw a line from the current (x,y) coordinate.

Example:

; SSSS -mYY YYYY YYYY | BBBB -mXX XXXX XXXX

87FE 73FE ; 1000 0111 1111 1110 | 0111 0011 1111 1110

; - SSSS is the local scale 0 .. 9 added to the global scale

; - BBBB is the brightness: 0 .. 15

; - m is 1 for negative or 0 for positive for the X and Y deltas

; - (x,y) is the coordinate delta for the vector

VEC scale=08(/2) bri=07 x=1022 y=-1022 (511.00, -511.00)

LABS

Set the current (x,y) and global scale-factor.

Example:

; 1010 00yy yyyy yyyy | SSSS 00xx xxxx xxxx

A37F 03FF ; 1010 0011 0111 1111 | 0000 0011 1111 1111

; - SSSS is the global scale 0 .. 15

; - (x,y) is the new (x,y) coordinate. This is NOT adjusted by SSSS.

CUR scale=00(/512) y=895 x=1023

HALT

End the current drawing list.

B000 ; 1011 0000 0000 0000 HALT

JSR

Jump to a vector subroutine. Note that there is room in the internal "stack" for only FOUR levels of nested subroutine calls. Be careful.

Note that the target address is the WORD address -- not the byte address.

Example:

; 1100 aaaa aaaa aaaa

CAE4 ; 1100 1010 1110 0100

; - a is the word address of the destination

In this case:

a = 0AE4

Multipy by two to get the word address: 0AE4 * 2 = 15C8

JSR $0AE4 ($15C8) ; Disassembly shows word and byte address

RTS

Return from current vector subroutine.

D000 ; 1101 0000 0000 0000 RTS

JMP

Jump to a new location in the vector program.

Note that the target address is the WORD address -- not the byte address.

Example:

; 1110 aaaa aaaa aaaa

EA0A ; 1110 1010 0000 1010

; - a is the word address of the destination

In this case:

a = 0A0A

Multipy by two to get the word address: 0A0A * 2 = 1414

JSR $0A0A ($1414) ; Disassembly shows word and byte address

SVEC

Use a "short" notation to draw a vector. This does not mean the vector itself is necessarily short. It means that the notation is shorter (fewer bits of resolution).

Example:

; 1111 smYY BBBB SmXX

FF70 ; 1111 1111 0111 0000

; - Ss (0=*2, 1=*4, 2=*8, 3=*16)

; - BBBB is the brightness: 0 .. 15

; - m is 1 for negative and 0 for positive for the X and Y

; - (x,y) is the coordinate change for the vector

SVEC scale=01(*2) bri=07 x=0 y=-3 (0.00, -6.00)